23. On Programming#

23.1. Programming as Language#

Learning to program means learning a new way to think – think like a computer scientist. This way of thinking combines some of the best features of mathematics, engineering, and natural science.

Like mathematicians, computer scientists use formal languages to denote ideas – specifically computations. Like engineers, they design things, assembling components into systems and evaluating trade-offs among alternatives. Like scientists, they observe the behavior of complex systems, form hypotheses, and test predictions.

We will start with the most basic elements of programming and work our way up. In this chapter, we’ll see how Python represents numbers, letters, and words. And you’ll learn to perform arithmetic operations.

You will also start to learn the vocabulary of programming, including terms like operator, expression, value, and type. This vocabulary is important – you will need it to understand the rest of the book, to communicate with other programmers, and to use and understand virtual assistants.

Natural languages are the languages people speak, like English, Spanish, and French. They were not designed by people; they evolved naturally.

Formal languages are languages that are designed by people for specific applications. For example, the notation that mathematicians use is a formal language that is particularly good at denoting relationships among numbers and symbols. Similarly, programming languages are formal languages that have been designed to express computations.

Although formal and natural languages have some features in common there are important differences:

Ambiguity: Natural languages are full of ambiguity, which people deal with by using contextual clues and other information. Formal languages are designed to be nearly or completely unambiguous, which means that any program has exactly one meaning, regardless of context.

Redundancy: In order to make up for ambiguity and reduce misunderstandings, natural languages use redundancy. As a result, they are often verbose. Formal languages are less redundant and more concise.

Literalness: Natural languages are full of idiom and metaphor. Formal languages mean exactly what they say.

Because we all grow up speaking natural languages, it is sometimes hard to adjust to formal languages. Formal languages are more dense than natural languages, so it takes longer to read them. Also, the structure is important, so it is not always best to read from top to bottom, left to right. Finally, the details matter. Small errors in spelling and punctuation, which you can get away with in natural languages, can make a big difference in a formal language.

23.2. Expressions and statements#

By definition, an expression is a combination of values, variables, operators, and function calls that the Python interpreter can evaluate to produce a single value. Note that a single value, like an integer, floating-point number, or string, can be an expression.

A statement is a unit of code that executes an action or command, or controls the flow of the program. They do not evaluate to a value that can be used elsewhere, like an expression. For example, an assignment statement creates a variable and gives it a value, but the statement itself has no value.

Computing the value of an expression is called evaluation; whereas running a statement is called execution.

This is an expression that includes several elements.:

19 + n + round(math.pi) * 2

This is a statement:

n = 17

So, a statement performs an action. An expression computes a value. For example:

Type |

Example |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Statement |

|

Assignment statement: Assigns 5 to |

|

Print statement: Prints something to the screen (has an effect); no value. |

|

|

|

|

|

Import the functionalities from the |

|

Expression |

|

Produces the value |

|

Computes a value based on |

|

|

Evaluates to |

Overall, the key differences between expressions and statements can be summarized as:

Feature |

Expression |

Statement |

|---|---|---|

Produces value |

Yes |

No |

Can be assigned |

var = expr |

No (e.g., |

Can be printed |

print(expr) |

No |

Used as argument |

func(expr) |

No |

Can be nested? |

Yes |

Limited |

6 + 6 ** 2

42

Notice that exponentiation happens before addition. Python follows the order of operations you might have learned in a math class: exponentiation happens before multiplication and division, which happen before addition and subtraction.

In the following example, multiplication happens before addition.

12 + 5 * 6

42

If you want the addition to happen first, you can use parentheses.

(12 + 5) * 6

102

Every expression has a value.

For example, the expression 6 * 7 has the value 42.

23.3. Python Operators#

In Python, operators are special symbols that perform computations or logical comparisons between values. They form the backbone of most expressions — whether you’re performing arithmetic, comparing data, assigning values, or testing relationships between objects.

23.3.1. Operators#

Type |

Operator |

Meaning |

Example |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Arithmetic |

|

Addition |

|

|

|

Subtraction |

|

|

|

|

Multiplication |

|

|

|

|

Division |

|

|

|

|

Floor Division |

|

|

|

|

Modulus |

|

|

|

|

Exponentiation |

|

|

|

2. Comparison |

|

Equal to |

|

|

|

Not equal to |

|

|

|

|

Greater than |

|

|

|

|

Less than |

|

|

|

|

Greater than or equal |

|

|

|

|

Less than or equal |

|

|

|

3. Logical |

|

Logical AND |

|

|

|

Logical OR |

|

|

|

|

Logical NOT |

|

|

|

4. Assignment |

|

Assign |

|

|

|

Add and assign |

|

|

|

|

Subtract and assign |

|

|

|

|

Multiply and assign |

|

|

|

|

Divide and assign |

|

|

|

|

Floor divide and assign |

|

|

|

|

Modulus and assign |

|

|

|

|

Exponent and assign |

|

|

|

|

Assignment expression (walrus operator) |

|

assign sum(data) to total |

|

5. Bitwise |

|

Bitwise AND |

|

|

|

Bitwise OR |

|

|

|

|

Bitwise XOR |

|

|

|

|

Bitwise NOT |

|

|

|

|

Left shift |

|

|

|

|

Right shift |

|

|

|

6. Membership |

|

Member of |

|

|

|

Not member of |

|

|

|

7. Identity |

|

Same object |

|

Varies |

|

Different object |

|

Varies |

23.3.2. Operator Precedence#

Operator precedence determines the order in which operations are evaluated in an expression. Operations with higher precedence are performed before those with lower precedence. Use parentheses () to override the default precedence.

Precedence Level |

Operator(s) |

Description / Example |

|

|---|---|---|---|

1 (Highest) |

|

Parentheses — control order of evaluation |

|

2 |

|

Exponentiation |

|

3 |

|

Unary plus, unary minus, bitwise NOT |

|

4 |

|

Multiplication, division, floor division, modulus |

|

5 |

|

Addition, subtraction |

|

6 |

|

Bitwise left and right shift |

|

7 |

|

Bitwise AND |

|

8 |

|

Bitwise XOR, bitwise OR |

|

9 |

Comparison: |

Relational and equality checks |

|

10 |

|

Identity and membership operators |

|

11 |

|

Logical NOT |

|

12 |

|

Logical AND |

|

13 |

|

Logical OR |

|

14 (Lowest) |

Assignment: |

Assignment and augmented assignment |

Note:

Always use parentheses when precedence is unclear to improve code readability

Exponentiation (

**) is evaluated right-to-left:2 ** 3 ** 2equals2 ** 9=512Comparison operators all have the same precedence and are evaluated left-to-right

Logical operators follow the order:

not→and→orWhen operators have the same precedence, they are typically evaluated left-to-right (left-associative), except for exponentiation which is right-associative.

### example of operator precedence

x = 1

y = 2

z = 3

result = x + y * z ** 2

print(result) ### output: 19

19

23.3.3. Arithmetic operators#

An arithmetic operator is a symbol that represents an arithmetic computation. For example, the plus sign, +, performs addition.

30 + 12

42

The minus sign, -, is the operator that performs subtraction.

43 - 1

42

The asterisk, *, performs multiplication.

6 * 7

42

And the forward slash, /, performs division:

84 / 2

42.0

Notice that the result of the division is 42.0 rather than 42. That’s because they are two types of numbers:

integers, which represent numbers with no fractional or decimal part, and

floating-point numbers, which represent integers and numbers with a decimal point.

If you add, subtract, or multiply two integers, the result is an integer. But if you divide two integers, the result is a floating-point number.

Python provides another operator, //, that performs integer/floor division.

The result of integer division is always an integer.

84 // 2

42

Integer division is also called “floor division” because it always rounds down (toward the “floor”).

85 // 2

42

Finally, the operator ** performs exponentiation; that is, it raises a

number to a power:

7 ** 2

49

In some other languages, the caret, ^, is used for exponentiation, but in Python

it is a bitwise operator called XOR.

If you are not familiar with bitwise operators, the result might be unexpected:

7 ^ 2

5

23.3.4. Bitwise Operations#

Bitwise operations are used for low-level programming tasks that require efficient manipulation of individual bits, such as optimizing arithmetic operations, flagging file permissions, and hashing.

For an example of Bitwise operations, let’s take a look at Bitwise AND(&). The bitwise AND operation returns 1 only if both bits are 1, as seen in the Truth Table below.

Truth Table:

A |

B |

A & B |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

a = 5 ### binary: 0101

b = 3 ### binary: 0011

result = a & b ### 0001 = 1

print(f"{a} & {b} = {result}") ### 5 & 3 = 1

print(f"binary: {bin(result)}") ### binary: 0b1 (0b/0B means Binary or Base 2)

5 & 3 = 1

binary: 0b1

As another example, we can use the bitwise operation to check if a number is even:

def is_even(n):

return (n & 1) == 0

23.3.5. Arithmetic functions#

In addition to the arithmetic operators, Python provides a few functions that work with numbers.

For example, the round function takes a floating-point number and rounds it off to the nearest integer.

round(42.4)

42

round(42.6)

43

The abs function computes the absolute value of a number.

For a positive number, the absolute value is the number itself.

abs(42)

42

For a negative number, the absolute value is positive.

abs(-42)

42

When we use a function like this, we say we’re calling the function. An expression that calls a function is a function call.

When you call a function, the parentheses are required. If you leave them out, you get an error message.

NOTE: The following cell uses %%expect, which is a Jupyter “magic command” that means we expect the code in this cell to produce an error. For more on this topic, see the

Jupyter notebook introduction .

%%expect SyntaxError

abs 42

UsageError: Cell magic `%%expect` not found.

You can ignore the first line of this message; it doesn’t contain any information we need to understand right now.

The second line is the code that contains the error, with a caret (^) beneath it to indicate where the error was discovered.

The last line indicates that this is a syntax error, which means that there is something wrong with the structure of the expression. In this example, the problem is that a function call requires parentheses.

Let’s see what happens if you leave out the parentheses and the value.

abs

<function abs(x, /)>

A function name all by itself is a legal expression that has a value.

When it’s displayed, the value indicates that abs is a function, and it includes some additional information I’ll explain later.

23.3.6. Strings#

In addition to numbers, Python can also represent sequences of letters, which are called strings because the letters are strung together like beads on a necklace. To write a string, we can put a sequence of letters inside straight quotation marks.

'Hello'

'Hello'

It is also legal to use double quotation marks.

"world"

'world'

Double quotes make it easy to write a string that contains an apostrophe, which is the same symbol as a straight quote.

"it's a small "

"it's a small "

Strings can also contain spaces, punctuation, and digits.

'Well, '

'Well, '

The + operator works with strings; it joins two strings into a single string, which is called concatenation

'Well, ' + "it's a small " + 'world.'

"Well, it's a small world."

The * operator also works with strings; it makes multiple copies of a string and concatenates them.

'Spam, ' * 4

'Spam, Spam, Spam, Spam, '

The other arithmetic operators don’t work with strings.

Python provides a function called len that computes the length of a string.

len('Spam')

4

Notice that len counts the letters between the quotes, but not the quotes.

When you create a string, be sure to use straight quotes. The back quote, also known as a backtick, causes a syntax error.

`Hello`

Cell In[27], line 1

`Hello`

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Smart quotes, also known as curly quotes, are also illegal.

‘Hello’

Cell In[28], line 1

‘Hello’

^

SyntaxError: invalid character '‘' (U+2018)

23.4. Data Types#

23.4.1. Values and Types#

So far we’ve seen three kinds of values:

2is an integer,42.0is a floating-point number, and'Hello'is a string.

A kind of value is called a type. Every value has a type – or we sometimes say it “belongs to” a type.

Python provides a function called type that tells you the type of any value.

The type of an integer is int.

type(2)

int

The type of a floating-point number is float.

type(42.0)

float

And the type of a string is str.

type('Hello, World!')

str

The types int, float, and str can be used as functions.

For example, int can take a floating-point number and convert it to an integer (always rounding down).

int(42.9)

42

And float can convert an integer to a floating-point value.

float(42)

42.0

Now, here’s something that can be confusing. What do you get if you put a sequence of digits in quotes?

'126'

'126'

It looks like a number, but it is actually a string.

type('126')

str

If you try to use it like a number, you might get an error.

%%expect TypeError

'126' / 3

UsageError: Cell magic `%%expect` not found.

This example generates a TypeError, which means that the values in the expression, which are called operands, have the wrong type.

The error message indicates that the / operator does not support the types of these values, which are str and int.

If you have a string that contains digits, you can use int to convert it to an integer.

int('126') / 3

42.0

If you have a string that contains digits and a decimal point, you can use float to convert it to a floating-point number.

float('12.6')

12.6

When you write a large integer, you might be tempted to use commas

between groups of digits, as in 1,000,000.

This is a legal expression in Python, but the result is not an integer.

1,000,000

(1, 0, 0)

Python interprets 1,000,000 as a comma-separated sequence of integers.

We’ll learn more about this kind of sequence later.

You can use underscores to make large numbers easier to read.

1_000_000

1000000

23.4.2. Built-in Data Types#

Data types define the kind of values you work with. Python has standard types built into the interpreter. The commonly used ones are:

No. |

Category |

Types |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Numeric Types |

|

Integer, floating-point, and complex numbers |

2 |

Boolean Type |

|

True/False logic |

3 |

Sequence Types |

|

Ordered, mutable/immutable collections; nesting supported |

4 |

Text Sequence |

|

Text that supports indexing and slicing |

5 |

Binary Sequence |

|

Binary data |

|

|||

6 |

Set Types |

|

Unordered collections of unique elements |

7 |

Mapping Type |

|

Key-value pairs |

8 |

None Type |

|

Represents absence of value |

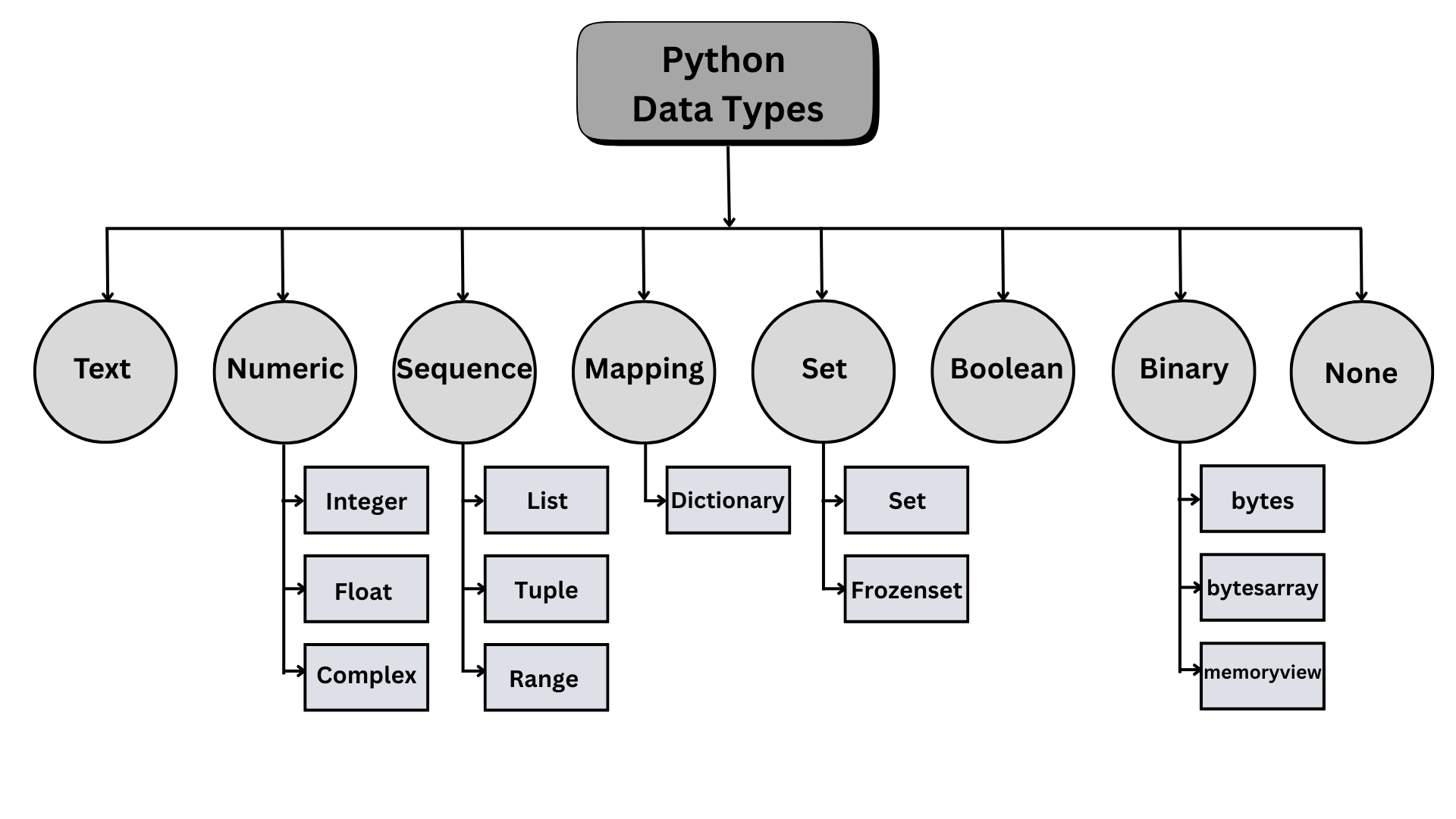

Fig. 23.1 Python built-in data types #

23.4.2.1. Numbers#

Python has three basic number types: the integer (e.g., 1), the floating point number (e.g., 1.0), and the complex number. Standard mathematical order of operation is followed for basic arithmetic operations. Note that dividing two integers results in a floating point number and dividing by zero will generate an error.

print(1 + 1)

print(1 * 3)

print(1 / 2)

print(2 / 2) ### output 1.0, not 1

print(2 ** 4)

2

3

0.5

1.0

16

The modulus operation (also known as the mod function) is represented by the percent sign. It returns what remains after the division:

print(4 % 2)

print(5 % 2)

print(9 // 2)

0

1

4

23.4.2.2. String Sequences#

Strings can be created using single or double quotes. You can also wrap double quotes around single quotes if you need to include a quote inside the string.

print('hello')

print("hello")

print("I can't go")

print('I can\'t go') ### escape sequence: \

hello

hello

I can't go

I can't go

Indexing and Slicing Strings

Strings are sequences of characters. You can access specific elements using square bracket notation. Python indexing starts at zero. Negative indexing in slicing starts with -1 from the end element.

s = 'hello'

print(s[0])

print(s[4])

print(s[-1])

h

o

o

Slice notation allows you to grab parts of a string. Use a colon to specify the start and stop indices. The stop index is not included.

s = 'applebananacherry'

print(s[0:]) ### applebananacherry

print(s[:5]) ### apple

print(s[5:11]) ### banana

print(s[-6:]) ### cherry

print(s[-6:0]) ###

print(s[-6:-1]) ### cherr (stop exclusive)

applebananacherry

apple

banana

cherry

cherr

23.4.2.3. Sequence: list#

Lists, just like tuple and range, are sequences of elements (similar to the array in many other languages) in square brackets, separated by commas.

my_list = ['a', 'b', 'c']

my_list.append('d')

my_list[0]

my_list[1:3]

my_list[0] = 'NEW'

Lists can contain any data type, including other lists (nested). You can access elements using list indexing. For nested lists, use chaining/stacking square brackets.

lst = [1, 2, [3, 4]]

lst[2][1] ### 4

nest = [1, 2, 3, [4, 5, ['target']]]

nest[3][2][0] ### 'target'

print(nest[3][2][0]) ### target

print(nest[3][2][0][0]) ### t (a list is a sequence)

target

t

23.4.2.4. Mapping: dictionary#

In Python, a mapping type is a collection that stores data as key–value pairs, where each key is unique and maps to a corresponding value. The most common mapping type is the dictionary (dict), which allows fast lookup, insertion, and modification of values using their keys rather than numerical indexes. An example of a Python dictionary:

student = {

"name": "Ava",

"age": 20,

"major": "Computer Science",

"is_enrolled": True,

"courses": [ "Python", "Data Structures", "Calculus" ]

}

student

{'name': 'Ava',

'age': 20,

'major': 'Computer Science',

'is_enrolled': True,

'courses': ['Python', 'Data Structures', 'Calculus']}

23.4.3. Type Casting#

A number of the built-in functions are constructor functions that can perform type casting. For example:

### literals: 1, 2.8, "3"

print(type(1), type(2.8), type("3"))

x = int(1) # x will be 1

y = int(2.8) # y will be 2

z = int("3") # z will be 3

print(x, y, z)

print(type(x), type(y), type(z))

<class 'int'> <class 'float'> <class 'str'>

1 2 3

<class 'int'> <class 'int'> <class 'int'>

23.5. Built-in Functions#

In Python, built-in functions and built-in modules are both part of the standard tools the language gives you—but they serve different purposes.

Built-in functions are ready to use without importing anything. They are automatically available in every Python program.

Python built-in functions are tools for quick operation (length, convert, output). They can be grouped by their purposes as:

Group |

Functions |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

Numbers & math |

|

|

Type constructors/conversions |

|

Convert or construct core types. |

Object/attribute introspection |

|

|

Attribute access |

|

Dynamic attribute management. |

Iteration & functional tools |

|

Prefer comprehensions when clearer. |

Sequence/char helpers |

|

|

I/O |

|

|

Formatting / representation |

|

Also see f-strings for formatting. |

Object model (OOP helpers) |

|

Define descriptors and class behaviors. |

Execution / metaprogramming |

|

Use with care; security concerns for untrusted input. |

Environment / namespaces |

|

Introspection of current namespaces. |

Help/debugging |

|

|

Import |

|

Low-level import; usually use |

23.6. Modules#

A module is a collection of variables and functions. Built-in modules are part of the Python Standard Library, but you must import them before use. They provide extra features: math, dates, OS access, file utilities, random numbers, etc.

To use a variable in a module, you have to use the dot operator (.) between the name of the module and the name of the variable.

For example, the Python math module provides a variable called pi that contains the value of the mathematical constant denoted \(\pi\). We can display its value like math.pi:

import math

print(math.pi)

math.pi

3.141592653589793

3.141592653589793

The math module also contains functions. For example, sqrt computes square roots:

math.sqrt(25)

5.0

And the pow function raises one number to the power of a second number.

math.pow(5, 2)

25.0

At this point we’ve seen two ways to raise a number to a power: we can use the math.pow function or the exponentiation operator, **.

Either one is fine, but the operator is used more often than the function.

To see a list of all the Python built-in modules, you can run help('modules') in Python shell or Jupyter Notebook:

help('modules')

Please wait a moment while I gather a list of all available modules...

IPython alabaster itertools rlcompleter

PIL antigravity jedi rpds

__future__ anyio jinja2 runpy

__hello__ appnope json sched

__phello__ argon2 json5 secrets

_abc argparse jsonpointer select

...

...

23.7. Debugging#

Programmers make mistakes. For whimsical reasons, programming errors are called bugs and the process of tracking them down is called debugging.

Programming, and especially debugging, sometimes brings out strong emotions. If you are struggling with a difficult bug, you might feel angry, sad, or embarrassed.

Preparing for these reactions might help you deal with them. One approach is to think of the computer as an employee with certain strengths, like speed and precision, and particular weaknesses, like lack of empathy and inability to grasp the big picture.

Your job is to be a good manager: find ways to take advantage of the strengths and mitigate the weaknesses. And find ways to use your emotions to engage with the problem, without letting your reactions interfere with your ability to work effectively.

Learning to debug can be frustrating, but it is a valuable skill that is useful for many activities beyond programming. At the end of each chapter there is a section, like this one, with my suggestions for debugging. I hope they help!

23.8. Glossary#

arithmetic operator

A symbol, like + and *, that denotes an arithmetic operation like addition or multiplication.

integer A type that represents numbers with no fractional or decimal part.

floating-point: A type that represents integers and numbers with decimal parts.

integer division

An operator, //, that divides two numbers and rounds down to an integer.

expression A combination of variables, values, and operators.

value An integer, floating-point number, or string – or one of other kinds of values we will see later.

function A named sequence of statements that performs some useful operation. Functions may or may not take arguments and may or may not produce a result.

function call An expression – or part of an expression – that runs a function. It consists of the function name followed by an argument list in parentheses.

syntax error An error in a program that makes it impossible to parse – and therefore impossible to run.

string A type that represents sequences of characters.

concatenation Joining two strings end-to-end.

type

A category of values.

The types we have seen so far are integers (type int), floating-point numbers (type float), and strings (type str).

operand One of the values on which an operator operates.

natural language Any of the languages that people speak that evolved naturally.

formal language Any of the languages that people have designed for specific purposes, such as representing mathematical ideas or computer programs. All programming languages are formal languages.

bug An error in a program.

debugging The process of finding and correcting errors.