20.6. Multiple Regression#

Now that we have explored ways to use multiple attributes to predict a categorical variable, let us return to predicting a quantitative variable. Predicting a numerical quantity is called regression, and a commonly used method to use multiple attributes for regression is called multiple linear regression.

20.6.1. Home Prices#

The following dataset of house prices and attributes was collected over several years for the city of Ames, Iowa. A description of the dataset appears online . We will focus only a subset of the columns. We will try to predict the sale price column from the other columns.

all_sales = pd.read_csv(path_data + 'house.csv')

# len(all_sales)

all_sales

| Order | PID | MS SubClass | MS Zoning | Lot Frontage | Lot Area | Street | Alley | Lot Shape | Land Contour | ... | Pool Area | Pool QC | Fence | Misc Feature | Misc Val | Mo Sold | Yr Sold | Sale Type | Sale Condition | SalePrice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 526301100 | 20 | RL | 141.0 | 31770 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0 | 5 | 2010 | WD | Normal | 215000 |

| 1 | 2 | 526350040 | 20 | RH | 80.0 | 11622 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | MnPrv | NaN | 0 | 6 | 2010 | WD | Normal | 105000 |

| 2 | 3 | 526351010 | 20 | RL | 81.0 | 14267 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | NaN | Gar2 | 12500 | 6 | 2010 | WD | Normal | 172000 |

| 3 | 4 | 526353030 | 20 | RL | 93.0 | 11160 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0 | 4 | 2010 | WD | Normal | 244000 |

| 4 | 5 | 527105010 | 60 | RL | 74.0 | 13830 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | MnPrv | NaN | 0 | 3 | 2010 | WD | Normal | 189900 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 2925 | 2926 | 923275080 | 80 | RL | 37.0 | 7937 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | GdPrv | NaN | 0 | 3 | 2006 | WD | Normal | 142500 |

| 2926 | 2927 | 923276100 | 20 | RL | NaN | 8885 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Low | ... | 0 | NaN | MnPrv | NaN | 0 | 6 | 2006 | WD | Normal | 131000 |

| 2927 | 2928 | 923400125 | 85 | RL | 62.0 | 10441 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | MnPrv | Shed | 700 | 7 | 2006 | WD | Normal | 132000 |

| 2928 | 2929 | 924100070 | 20 | RL | 77.0 | 10010 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0 | 4 | 2006 | WD | Normal | 170000 |

| 2929 | 2930 | 924151050 | 60 | RL | 74.0 | 9627 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | ... | 0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0 | 11 | 2006 | WD | Normal | 188000 |

2930 rows × 82 columns

all_sales.describe()

| Order | PID | MS SubClass | Lot Frontage | Lot Area | Overall Qual | Overall Cond | Year Built | Year Remod/Add | Mas Vnr Area | ... | Wood Deck SF | Open Porch SF | Enclosed Porch | 3Ssn Porch | Screen Porch | Pool Area | Misc Val | Mo Sold | Yr Sold | SalePrice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 2930.00000 | 2.930000e+03 | 2930.000000 | 2440.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2907.000000 | ... | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 | 2930.000000 |

| mean | 1465.50000 | 7.144645e+08 | 57.387372 | 69.224590 | 10147.921843 | 6.094881 | 5.563140 | 1971.356314 | 1984.266553 | 101.896801 | ... | 93.751877 | 47.533447 | 23.011604 | 2.592491 | 16.002048 | 2.243345 | 50.635154 | 6.216041 | 2007.790444 | 180796.060068 |

| std | 845.96247 | 1.887308e+08 | 42.638025 | 23.365335 | 7880.017759 | 1.411026 | 1.111537 | 30.245361 | 20.860286 | 179.112611 | ... | 126.361562 | 67.483400 | 64.139059 | 25.141331 | 56.087370 | 35.597181 | 566.344288 | 2.714492 | 1.316613 | 79886.692357 |

| min | 1.00000 | 5.263011e+08 | 20.000000 | 21.000000 | 1300.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1872.000000 | 1950.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 2006.000000 | 12789.000000 |

| 25% | 733.25000 | 5.284770e+08 | 20.000000 | 58.000000 | 7440.250000 | 5.000000 | 5.000000 | 1954.000000 | 1965.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.000000 | 2007.000000 | 129500.000000 |

| 50% | 1465.50000 | 5.354536e+08 | 50.000000 | 68.000000 | 9436.500000 | 6.000000 | 5.000000 | 1973.000000 | 1993.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 27.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 6.000000 | 2008.000000 | 160000.000000 |

| 75% | 2197.75000 | 9.071811e+08 | 70.000000 | 80.000000 | 11555.250000 | 7.000000 | 6.000000 | 2001.000000 | 2004.000000 | 164.000000 | ... | 168.000000 | 70.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 8.000000 | 2009.000000 | 213500.000000 |

| max | 2930.00000 | 1.007100e+09 | 190.000000 | 313.000000 | 215245.000000 | 10.000000 | 9.000000 | 2010.000000 | 2010.000000 | 1600.000000 | ... | 1424.000000 | 742.000000 | 1012.000000 | 508.000000 | 576.000000 | 800.000000 | 17000.000000 | 12.000000 | 2010.000000 | 755000.000000 |

8 rows × 39 columns

sales1 = all_sales[all_sales['Bldg Type'] == '1Fam']

sales2 = sales1[sales1['Sale Condition'] == 'Normal']

sales = sales2[['SalePrice', '1st Flr SF', '2nd Flr SF',

'Total Bsmt SF', 'Garage Area',

'Wood Deck SF', 'Open Porch SF', 'Lot Area',

'Year Built', 'Yr Sold']]

sales = sales.sort_values(by=['SalePrice'])

len(sales)

2002

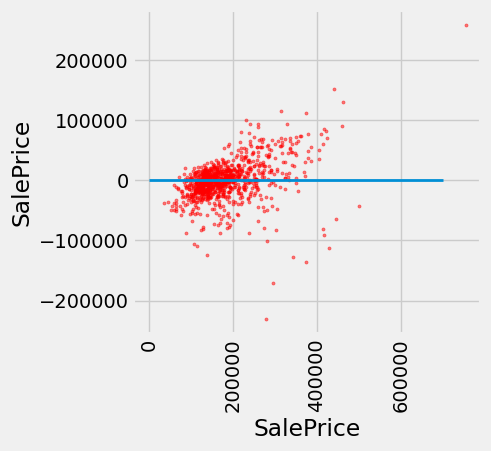

A histogram of sale prices shows a large amount of variability and a distribution that is clearly not normal. A long tail to the right contains a few houses that had very high prices. The short left tail does not contain any houses that sold for less than $35,000.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,4))

ax.hist(sales['SalePrice'], bins=32, density=True, alpha=0.8, ec='white', zorder=5)

unit = '$'

y_label = 'Percent per ' + (unit if unit else 'unit')

x_label = 'SalesPrice ($)'

plt.ylabel(y_label, fontsize=12)

plt.xlabel(x_label, fontsize=12)

x_min, x_max = sales['SalePrice'].min(), sales['SalePrice'].max() ### multiple assignment

ax.set_xticks(np.linspace(x_min, x_max+.01, 32))

# ax.set_xticks(np.linspace(0, 800000, 9))

plt.xticks(rotation=90, fontsize=8)

plt.yticks(fontsize=10)

y_vals = ax.get_yticks()

ax.set_yticks(y_vals)

ax.set_yticklabels(['{:g}'.format(x * 100) for x in y_vals])

plt.title('');

plt.show()

20.6.1.1. Correlation#

No single attribute is sufficient to predict the sale price. For example, the area of first floor, measured in square feet, correlates with sale price but only explains some of its variability.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,4))

ax.scatter(

sales['1st Flr SF'],

sales['SalePrice'],

color='darkblue',

alpha=0.8,

s=5

)

x_label = '1st Flr SF'

y_label = 'SalePrice'

plt.ylabel(y_label)

plt.xlabel(x_label)

plt.show()

correlation(sales, 'SalePrice', '1st Flr SF')

0.6424662541030225

In fact, none of the individual attributes have a correlation with sale price that is above 0.7 (except for the sale price itself).

for label in sales.columns:

print('Correlation of', label, 'and SalePrice:\t', correlation(sales, label, 'SalePrice'))

Correlation of SalePrice and SalePrice: 1.0

Correlation of 1st Flr SF and SalePrice: 0.6424662541030225

Correlation of 2nd Flr SF and SalePrice: 0.3575218942800824

Correlation of Total Bsmt SF and SalePrice: 0.652978626757169

Correlation of Garage Area and SalePrice: 0.6385944852520442

Correlation of Wood Deck SF and SalePrice: 0.3526986661950491

Correlation of Open Porch SF and SalePrice: 0.3369094170263733

Correlation of Lot Area and SalePrice: 0.29082345511576946

Correlation of Year Built and SalePrice: 0.5651647537135916

Correlation of Yr Sold and SalePrice: 0.025948579080721124

However, combining attributes can provide higher correlation. In particular, if we sum the first floor and second floor areas, the result has a higher correlation than any single attribute alone.

sales_copy = sales.copy()

both_floors = sales_copy.iloc[:,1] + sales_copy.iloc[:,2]

sales_copy['Both Floors'] = both_floors

correlation(sales_copy, 'SalePrice', 'Both Floors')

0.7821920556134877

# sales_copy.iloc[:,2]

# sales_copy['2nd Flr SF']

This high correlation indicates that we should try to use more than one attribute to predict the sale price. In a dataset with multiple observed attributes and a single numerical value to be predicted (the sale price in this case), multiple linear regression can be an effective technique.

20.6.2. Multiple Linear Regression#

In multiple linear regression, a numerical output is predicted from numerical input attributes by multiplying each attribute value by a different slope, then summing the results. In this example, the slope for the 1st Flr SF would represent the dollars per square foot of area on the first floor of the house that should be used in our prediction.

Before we begin prediction, we split our data randomly into a training and test set of equal size.

20.6.2.1. Train/Test split#

sales_copy = sales.copy()

train = sales_copy.sample(1001, replace=False)

test = sales_copy.drop(train.index)

print(f"{len(train)} training and {len(test)} test instances.")

1001 training and 1001 test instances.

20.6.2.2. Function for train/test split#

def split(self, k):

if not 1 <= k <= (len(self) - 1):

raise ValueError("Invalid value of k. k must be between 1 and the"

"number of rows - 1")

rows = np.random.permutation(len(self)) ### random shuffle of indices

first = self.take(rows[:k]) ### first k random rows → training set

rest = self.take(rows[k:]) ### remaining random rows → test set

return (first, rest) ### return a single tuple object

train, test = split(sales, 1001)

print(len(train), 'training and', len(test), 'test instances.')

1001 training and 1001 test instances.

20.6.2.3. The scikit learn way#

We could employ the scikit learn train_test_split function to determine the train, test split.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

train, test = train_test_split(sales_copy, test_size=0.5)

print(len(train), 'training and', len(test), 'test instances.')

1001 training and 1001 test instances.

The slopes in multiple regression is an array that has one slope value for each attribute in an example. Predicting the sale price involves multiplying each attribute by the slope and summing the result.

def predict(slopes, row):

return sum(slopes * np.array(row))

example_row1 = test.drop(columns=['SalePrice'])

example_row = example_row1.iloc[0]

print('Predicting sale price for:')

print(example_row)

example_slopes = np.random.normal(10, 1, len(example_row))

print('\nUsing slopes:\n', example_slopes)

print('\nResult:', predict(example_slopes, example_row))

Predicting sale price for:

1st Flr SF 1567.0

2nd Flr SF 0.0

Total Bsmt SF 1567.0

Garage Area 714.0

Wood Deck SF 264.0

Open Porch SF 32.0

Lot Area 9819.0

Year Built 1977.0

Yr Sold 2009.0

Name: 987, dtype: float64

Using slopes:

[11.23921808 11.6901262 10.10896541 9.80418403 11.57473382 8.55530722

10.69362051 10.34192697 8.8555199 ]

Result: 187019.67939760862

The result is an estimated sale price, which can be compared to the actual sale price to assess whether the slopes provide accurate predictions. Since the example_slopes above were chosen at random, we should not expect them to provide accurate predictions at all.

print('Actual sale price:', test['SalePrice'].iloc[0])

print('Predicted sale price using random slopes:', predict(example_slopes, example_row))

Actual sale price: 196000

Predicted sale price using random slopes: 187019.67939760862

20.6.2.4. Least Squares Regression#

The next step in performing multiple regression is to define the least squares objective. We perform the prediction for each row in the training set, and then compute the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the predictions from the actual prices.

train_prices = train.iloc[:,0]

train1 = train.copy()

train_attributes = train1.drop(train1.columns[0], axis=1)

def rmse(slopes, attributes, prices):

errors = []

for i in np.arange(len(prices)):

predicted = predict(slopes, attributes.iloc[i])

actual = prices.iloc[i]

errors.append((predicted - actual) ** 2)

return np.mean(errors) ** 0.5

def rmse_train(slopes):

return rmse(slopes, train_attributes, train_prices)

print('RMSE of all training examples using random slopes:', rmse_train(example_slopes))

RMSE of all training examples using random slopes: 82740.47779366456

Finally, we use the minimize function to find the slopes with the lowest RMSE. Since the function we want to minimize, rmse_train, takes an array instead of a number, we must pass the array=True argument to minimize. When this argument is used, minimize also requires an initial guess of the slopes so that it knows the dimension of the input array. Finally, to speed up optimization, we indicate that rmse_train is a smooth function using the smooth=True attribute. Computation of the best slopes may take several minutes.

from scipy import optimize

def minimize(f, start=None, smooth=False, log=None, array=False, **vargs):

"""Minimize a function f of one or more arguments.

Args:

f: A function that takes numbers and returns a number

start: A starting value or list of starting values

smooth: Whether to assume that f is smooth and use first-order info

log: Logging function called on the result of optimization (e.g. print)

vargs: Other named arguments passed to scipy.optimize.minimize

Returns either:

(a) the minimizing argument of a one-argument function

(b) an array of minimizing arguments of a multi-argument function

"""

if start is None:

assert not array, "Please pass starting values explicitly when array=True"

arg_count = f.__code__.co_argcount

assert arg_count > 0, "Please pass starting values explicitly for variadic functions"

start = [0] * arg_count

if not hasattr(start, '__len__'):

start = [start]

if array:

objective = f

else:

@functools.wraps(f)

def objective(args):

return f(*args)

if not smooth and 'method' not in vargs:

vargs['method'] = 'Powell'

result = optimize.minimize(objective, start, **vargs)

if log is not None:

log(result)

if len(start) == 1:

return result.x.item(0)

else:

return result.x

best_slopes = minimize(rmse_train, start=example_slopes, smooth=True, array=True)

train_df = pd.DataFrame(columns=[train_attributes.columns])

train_df.loc[0] = best_slopes

print('The best slopes for the training set:')

train_df

The best slopes for the training set:

| 1st Flr SF | 2nd Flr SF | Total Bsmt SF | Garage Area | Wood Deck SF | Open Porch SF | Lot Area | Year Built | Yr Sold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 74.661368 | 71.923473 | 47.84372 | 57.502788 | 33.09423 | 13.849907 | 0.40374 | 507.372344 | -504.880641 |

print(f'RMSE of all training examples using the best slopes: {rmse_train(best_slopes)}')

RMSE of all training examples using the best slopes: 30617.770698924305

20.6.2.5. Interpreting Multiple Regression#

Let’s interpret these results. The best slopes give us a method for estimating the price of a house from its attributes. A square foot of area on the first floor is worth about $75 (the first slope), while one on the second floor is worth about $70 (the second slope). The final negative value describes the market: prices in later years were lower on average.

The RMSE of around $30,000 means that our best linear prediction of the sale price based on all of the attributes is off by around $30,000 on the training set, on average. We find a similar error when predicting prices on the test set, which indicates that our prediction method will generalize to other samples from the same population.

test_prices = test.iloc[:,0]

test_attributes = test.drop(test.columns[0], axis=1)

test_attributes

| 1st Flr SF | 2nd Flr SF | Total Bsmt SF | Garage Area | Wood Deck SF | Open Porch SF | Lot Area | Year Built | Yr Sold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2843 | 498 | 0 | 498.0 | 216.0 | 0 | 0 | 8088 | 1922 | 2006 |

| 1901 | 334 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 5000 | 1946 | 2007 |

| 708 | 612 | 0 | 0.0 | 308.0 | 0 | 0 | 5925 | 1940 | 2009 |

| 1220 | 729 | 0 | 270.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 4130 | 1935 | 2008 |

| 1546 | 796 | 0 | 796.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 3636 | 1922 | 2008 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 2341 | 2000 | 0 | 1910.0 | 722.0 | 351 | 102 | 18261 | 2005 | 2006 |

| 2450 | 1933 | 1567 | 1733.0 | 959.0 | 870 | 86 | 17242 | 1993 | 2006 |

| 1063 | 2470 | 0 | 2535.0 | 789.0 | 154 | 65 | 12720 | 2003 | 2008 |

| 2445 | 1831 | 1796 | 1930.0 | 807.0 | 361 | 76 | 35760 | 1995 | 2006 |

| 1767 | 2444 | 1872 | 2444.0 | 832.0 | 382 | 50 | 21535 | 1994 | 2007 |

1001 rows × 9 columns

Now we use the best_slopes from the training set in the test.

test_prices = test.iloc[:,0]

test_attributes = test.drop(test.columns[0], axis=1)

def rmse_test(slopes):

return rmse(slopes, test_attributes, test_prices)

rmse_linear = rmse_test(best_slopes)

print('Test set RMSE for multiple linear regression:', rmse_linear)

Test set RMSE for multiple linear regression: 31591.821870325915

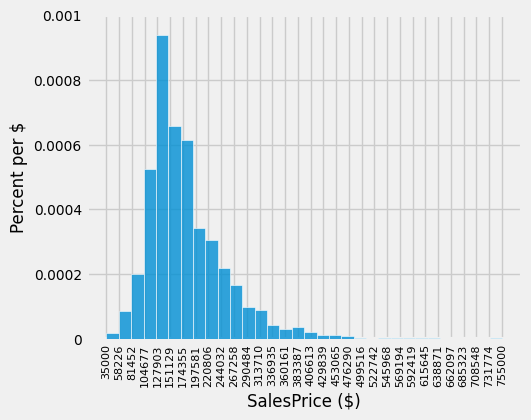

If the predictions were perfect, then a scatter plot of the predicted and actual values would be a straight line with slope 1. We see that most dots fall near that line, but there is some error in the predictions.

def fit(row):

return sum(best_slopes * np.array(row))

test['Fitted'] = test_attributes.apply(fit, axis=1)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(4,4))

ax.scatter(

test['Fitted'],

test['SalePrice'],

color='navy',

alpha=0.5,

s=10

)

x_label = 'Fitted'

y_label = 'SalePrice'

plt.ylabel(y_label)

plt.xlabel(x_label)

plt.plot([0, 5e5], [0, 5e5], lw=2)

plt.show()

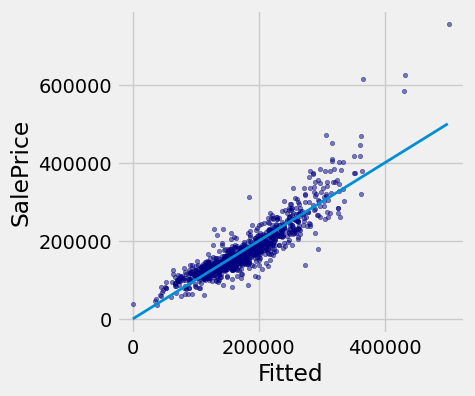

A residual plot for multiple regression typically compares the errors (residuals) to the actual values of the predicted variable. We see in the residual plot below that we have systematically underestimated the value of expensive houses, shown by the many positive residual values on the right side of the graph.

test['Residual'] = test_prices-test_attributes.apply(fit, axis=1)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(4,4))

ax.scatter(

test['SalePrice'],

test['Residual'],

color='navy',

alpha=0.5,

s=10

)

x_label = 'SalePrice'

y_label = 'SalePrice'

plt.ylabel(y_label)

plt.xlabel(x_label)

plt.xticks(rotation=90)

plt.plot([0, 7e5], [0, 0], lw=2)

plt.show()

As with simple linear regression, interpreting the result of a predictor is at least as important as making predictions. There are many lessons about interpreting multiple regression that are not included in this textbook. A natural next step after completing this text would be to study linear modeling and regression in further depth.

20.6.3. Nearest Neighbors for Regression#

Another approach to predicting the sale price of a house is to use the price of similar houses. This nearest neighbor approach is very similar to our classifier. To speed up computation, we will only use the attributes that had the highest correlation with the sale price in our original analysis.

train_nn = train.iloc[:, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8]]

test_nn = test.iloc[:, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8]]

train_nn

| SalePrice | 1st Flr SF | 2nd Flr SF | Total Bsmt SF | Garage Area | Year Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2142 | 127000 | 864 | 0 | 864.0 | 576.0 | 1972 |

| 2201 | 148500 | 567 | 531 | 531.0 | 216.0 | 1930 |

| 2643 | 110000 | 813 | 0 | 813.0 | 270.0 | 1930 |

| 1703 | 317000 | 1143 | 1330 | 1143.0 | 852.0 | 2004 |

| 26 | 126000 | 882 | 0 | 882.0 | 525.0 | 1970 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 867 | 198500 | 840 | 885 | 840.0 | 550.0 | 2002 |

| 1396 | 152400 | 864 | 486 | 576.0 | 627.0 | 1941 |

| 1222 | 87000 | 453 | 453 | 348.0 | 231.0 | 1937 |

| 691 | 115000 | 818 | 406 | 818.0 | 210.0 | 1926 |

| 2149 | 200000 | 860 | 869 | 860.0 | 542.0 | 2002 |

1001 rows × 6 columns

The computation of closest neighbors is identical to a nearest-neighbor classifier. In this case, we will exclude the 'SalePrice' rather than the 'Class' column from the distance computation. The five nearest neighbors of the first test row are shown below.

def distance(pt1, pt2):

"""The distance between two points, represented as arrays."""

return np.sqrt(np.sum((pt1 - pt2) ** 2))

def row_distance(row1, row2):

"""The distance between two rows of a table."""

return distance(np.array(row1), np.array(row2))

def distances(training, example, output):

"""Compute the distance from example for each row in training."""

dists = []

attributes = training.drop(columns=[output])

for row in range(len(attributes)):

dists.append(row_distance(attributes.iloc[row], example))

training['Distance'] = dists

#print(training)

return training

def closest(training, example, k, output):

"""Return a table of the k closest neighbors to example."""

distance = distances(training, example, output).sort_values(by=['Distance']).take(np.arange(k))

return distance

train_nn_A = train_nn.copy()

example_nn_row = test_nn.drop(test_nn.columns[0], axis=1).iloc[0]

closest(train_nn_A, example_nn_row, 5, 'SalePrice')

| SalePrice | 1st Flr SF | 2nd Flr SF | Total Bsmt SF | Garage Area | Year Built | Distance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 141 | 165500 | 1700 | 0 | 1398.0 | 447.0 | 1959 | 72.270326 |

| 375 | 200000 | 1671 | 0 | 1427.0 | 484.0 | 1978 | 112.058021 |

| 578 | 150000 | 1620 | 0 | 1281.0 | 490.0 | 1976 | 117.209215 |

| 2715 | 180000 | 1721 | 0 | 1461.0 | 440.0 | 1968 | 132.653684 |

| 1183 | 290000 | 1671 | 0 | 1426.0 | 550.0 | 1976 | 138.859641 |

One simple method for predicting the price is to average the prices of the nearest neighbors.

example_nn_row

1st Flr SF 1721.0

2nd Flr SF 0.0

Total Bsmt SF 1331.0

Garage Area 464.0

Year Built 1957.0

Name: 1924, dtype: float64

def predict_nn(example):

"""Return the majority class among the k nearest neighbors."""

train_nn_B = train_nn.copy()

col_sales_price = closest(train_nn_B, example, 5, 'SalePrice')

return np.average(col_sales_price['SalePrice'])

predict_nn(example_nn_row)

np.float64(197100.0)

Finally, we can inspect whether our prediction is close to the true sale price for our one test example. Looks reasonable!

print('Actual sale price:', test_nn['SalePrice'].iloc[0])

print('Predicted sale price using nearest neighbors:', predict_nn(example_nn_row))

Actual sale price: 174850

Predicted sale price using nearest neighbors: 197100.0

20.6.3.1. Evaluation#

To evaluate the performance of this approach for the whole test set, we apply predict_nn to each test example, then compute the root mean squared error of the predictions. Computation of the predictions may take several minutes.

def predict_nn(example):

"""Return the majority class among the k nearest neighbors."""

train_nn_B = train_nn.copy()

col_sales_price = closest(train_nn_B, example, 5, 'SalePrice')

return np.average(col_sales_price['SalePrice']).item(0)

predict_nn(example_nn_row)

197100.0

test_nn_C = test_nn.copy()

test_nn_drop = test_nn_C.drop(columns=['SalePrice'])

nn_test_predictions = test_nn_drop.apply(predict_nn, axis=1)

rmse_nn = np.mean((test_prices - nn_test_predictions) ** 2) ** 0.5

print('Test set RMSE for multiple linear regression: ', rmse_linear)

print('Test set RMSE for nearest neighbor regression:', rmse_nn)

Test set RMSE for multiple linear regression: 30125.47384508643

Test set RMSE for nearest neighbor regression: 33266.600357451876

For these data, the errors of the two techniques are quite similar! For different data sets, one technique might outperform another. By computing the RMSE of both techniques on the same data, we can compare methods fairly. One note of caution: the difference in performance might not be due to the technique at all; it might be due to the random variation due to sampling the training and test sets in the first place.

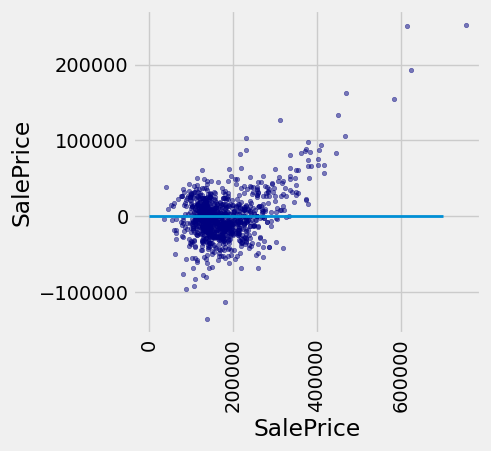

Finally, we can draw a residual plot for these predictions. We still underestimate the prices of the most expensive houses, but the bias does not appear to be as systematic. However, fewer residuals are very close to zero, indicating that fewer prices were predicted with very high accuracy.

test['Residual'] = test_prices-nn_test_predictions

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(4,4))

ax.scatter(

test['SalePrice'],

test['Residual'],

color='red',

alpha=0.5,

s=5

)

x_label = 'SalePrice'

y_label = 'SalePrice'

plt.ylabel(y_label)

plt.xlabel(x_label)

plt.xticks(rotation=90)

plt.plot([0, 7e5], [0, 0], lw=2)

plt.show()