3.1. Python Basics#

3.1.1. Variables#

Variables are names that reference objects in memory. You create them with the assignment operator (the equal sign, e.g., x = 2) and can reassign them to different objects. Use descriptive, lowercase names with underscores for readability, avoid starting names with digits or symbols.

Note

Object? In Python, a variable is a symbolic name or label that refers to an object in memory. In Python, everything is an object. This includes numbers, strings, lists, dictionaries, functions, classes, and even modules. An object is an instance of a class, which serves as a blueprint defining the object’s attributes (data) and methods. Each object has a unique identity (memory address), a type (its class), and a value. (see PEP 8 for Python coding conventions)

3.1.1.1. Variable Assignments#

Variables are assigned using the equal sign. Choose a variable name and assign an object or data type to it.

var = 2

x = 2

y = 3

x + y

x = x + x

Variable names should not start with numbers or special symbols. Use lowercase letters, and to chain together multiple words, use underscores.

#12var = 12

#$var = 5

name_of_var = 10

3.1.2. Operators#

Operators let you perform common processing on variables. There are 7 main operators:

assignment operators perform assignments and augmented assignments (e.g.,

=, +=).arithmetic operators perform calculations (e.g.,

+,-,*,/,%,**) (note that / yields a floating-point and you usually can’t divide by 0).comparison operators evaluate relationships (e.g.,

==,!=,<,>,<=,>=).logical operators combine boolean expressions (

and,or,not; e.g.,x == x and y > z).bitwise operators (

&,|,^,<<,>>; e.g.,x & y).identity operators compare the objects whereas the equality operator compare two values (

is,is not(e.g.,a is b)).membership operators (

in, not in(x in my_list)1).

Operator precedence: Python follows standard mathematical order of operations (PEMDAS: Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication and Division from left to right, then Addition and Subtraction from left to right). For example:

2 + 3 * 5 + 5

2 + 3 * (5 + 5)

The modulus operation (also known as the mod function) is represented by the percent sign in Python. It returns what remains after the division. Modulus is useful in the operations of cycles/repetition and clock arithmetic.

4 % 2

5 % 2

8 % 2

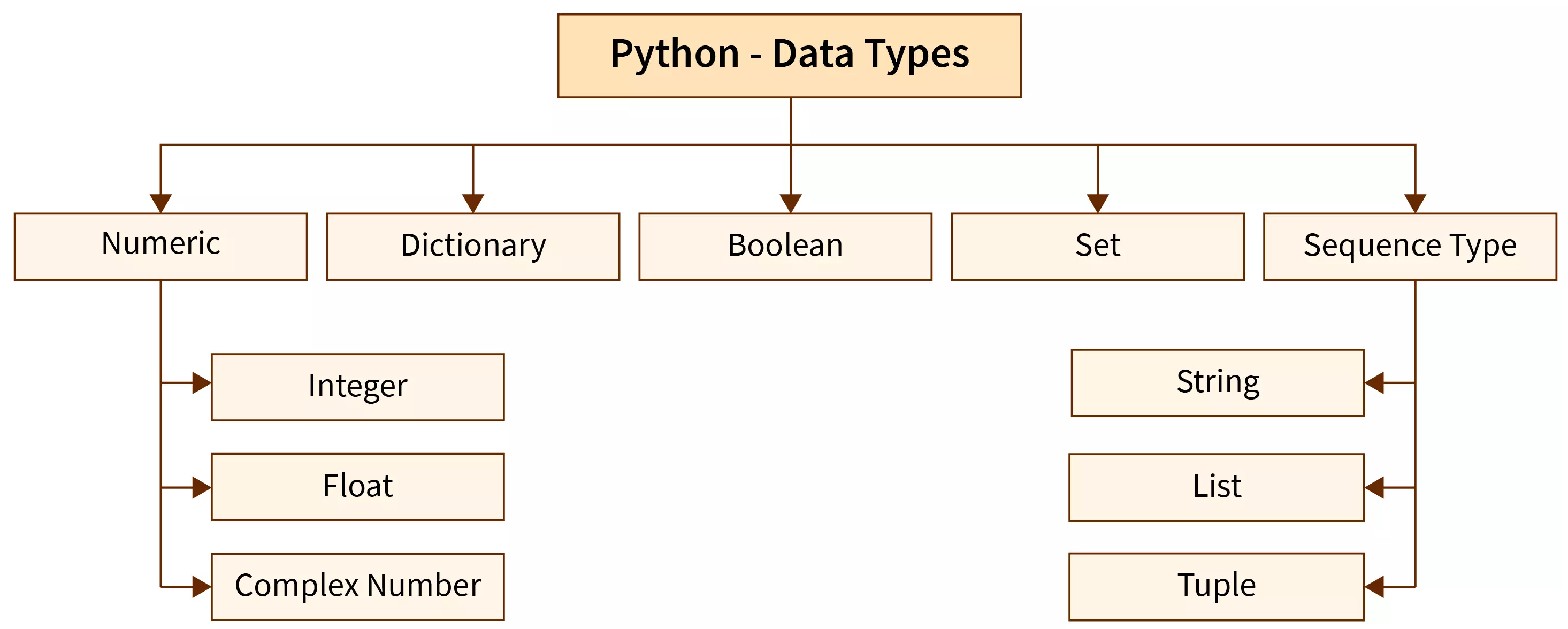

3.1.3. Data Types#

Data types define the kind of values you work with. Python has standard types built into the interpreter. The commonly used ones are:

numerics:

int,float,complexboolean:

bool(for true/false logic)sequence:

list,tuple,range(lists are ordered, mutable collections allowing nesting and various types for elements)text sequence:

str(note that strings for text that support indexing and slicing)set: set, frozenset

mapping: map

Fig. 3.1 Python built-in data types #

3.1.3.1. Numbers#

Python has three basic number types: the integer (e.g., 1), the floating point number (e.g., 1.0), and the complex number. Standard mathematical order of operation is followed for basic arithmetic operations. Note that dividing two integers results in a floating point number and dividing by zero will generate an error.

1 + 1

1 * 3

1 / 2

2 / 2 ### output 1.0, not 1

2 ** 4

2 + 3 * 5 + 5 ### 22

2 + 3 * (5 + 5) ### 32

The modulus operation (also known as the mod function) is represented by the percent sign. It returns what remains after the division:

4 % 2

5 % 2

8 % 2

3.1.3.2. Strings#

Strings can be created using single or double quotes. You can also wrap double quotes around single quotes if you need to include a quote inside the string.

'hello'

"hello"

"I can't go"

3.1.3.2.1. Indexing and Slicing Strings#

Strings are sequences of characters. You can access specific elements using square bracket notation. Python indexing starts at zero.

s = 'hello'

s[0]

s[4]

Slice notation allows you to grab parts of a string. Use a colon to specify the start and end indices. The end index is not included.

s = 'abcdefghijk'

s[0:]

s[:3]

s[3:6]

3.1.3.3. Lists#

Lists are sequences of elements (similar to the array in many other languages) in square brackets, separated by commas. Lists can contain any data type, including other lists.

my_list = ['a', 'b', 'c']

my_list.append('d')

my_list[0]

my_list[1:3]

my_list[0] = 'NEW'

Lists can be nested inside each other. You can access elements in nested lists by chaining square brackets.

lst = [1, 2, [3, 4]]

lst[2][1] ### 4

For deeper nesting, continue stacking brackets to access the desired element.

nest = [1, 2, 3, [4, 5, ['target']]]

nest[3][2][0] ### 'target'

print(nest[3][2][0]) ### target

3.1.4. Keywords and Built-in Functions#

3.1.4.1. Python Keywords#

In programming, keywords are predefined, reserved words with special meanings that define the structure and syntax of a programming language. Keywords have predefined meanings and cannot be used as identifiers (such as variable names, function names, or class names). For example, trying to create a value with a keyword as the variable name will cause a syntax error:

>>> True = "this is true"

File "<python-input-0>", line 1

True = "this is true"

^^^^

SyntaxError: cannot assign to True

>>>

There are currently 35 keywords and four soft keywords in Python.

False

await

else

import

pass

None

break

except

in

raise

True

class

finally

is

return

and

continue

for

lambda

try

as

def

from

nonlocal

while

assert

del

global

not

with

async

elif

if

or

yield

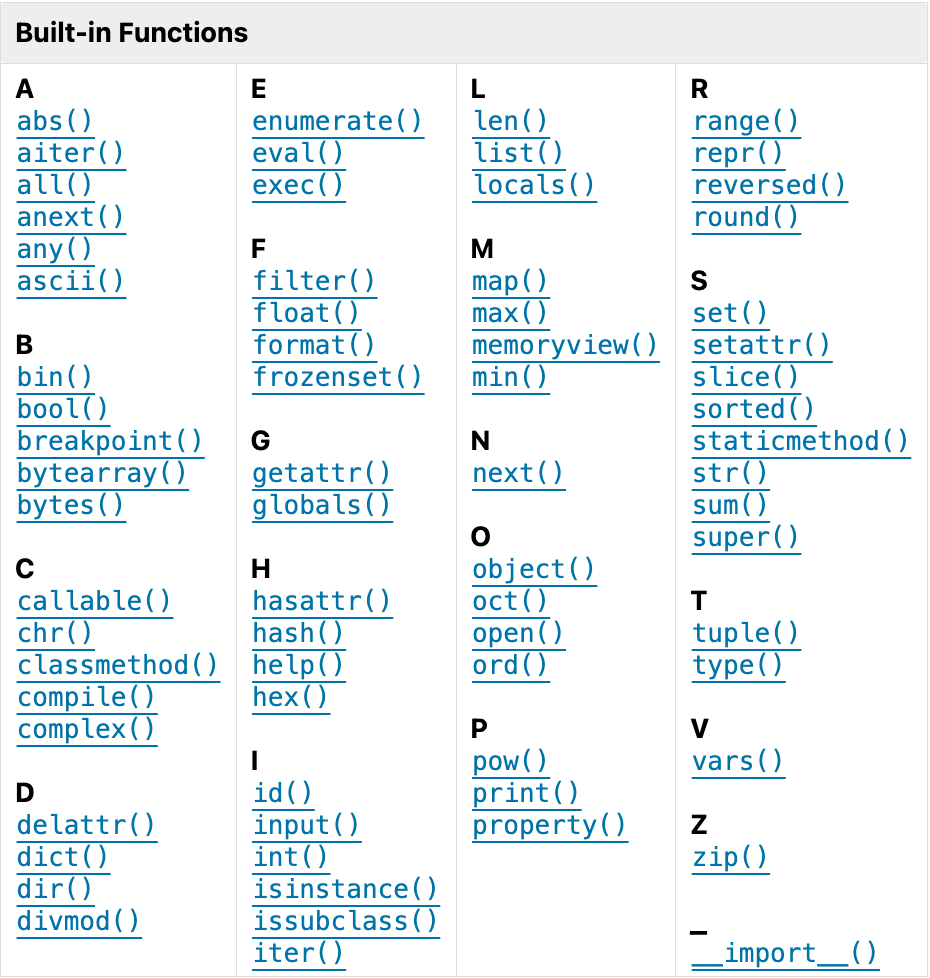

3.1.4.2. Python Built-iin Functions#

The Python interpreter has a number of functions and types built into it that are always available. Built-iin functions come prepackaged with the language and are ready-to-use, so you don’t need to import any modules to access them. Built-in functions represent the essential capabilities of the programming language such as:

working with data types

performing calculations

handling input/output

Some examples of built-in functions are:

print()) for displaying output)len()for finding the length of a sequencetype()for checking the data type of a valuerange()for generating sequences of numbersinput()for reading user input

A number of the built-in functions are constructor functions that can perform type casting. For example:

>>> x = int(1) # x will be 1

>>> y = int(2.8) # y will be 2

>>> z = int("3") # z will be 3

Fig. 3.2 Python Built-iin Functions #

These Python built-in functions can be grouped as:

Group |

Functions |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

Numbers & math |

|

|

Type constructors / conversions |

|

Convert or construct core types. |

Object/attribute introspection |

|

|

Attribute access |

|

Dynamic attribute management. |

Iteration & functional tools |

|

Prefer comprehensions when clearer. |

Sequence/char helpers |

|

|

I/O |

|

|

Formatting / representation |

|

Also see f-strings for formatting. |

Object model (OOP helpers) |

|

Define descriptors and class behaviors. |

Execution / metaprogramming |

|

Use with care; security concerns for untrusted input. |

Environment / namespaces |

|

Introspection of current namespaces. |

Help/debugging |

|

|

Import |

|

Low-level import; usually use |

3.1.5. Input and Output#

In Python, basic input and output operations are handled primarily by the input() and print() functions.

3.1.5.1. input()#

The input() function is used to obtain user input from the command line. It displays a prompt for the user to enter text and press Enter. The function then returns the entered text as a string.

name = input("Enter your name: ")

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

>>> num = input("Enter an integer between 1 and 10: ")

Enter an integer between 1 and 10: 7

>>> num

'7'

>>> type(num)

<class 'str'>

>>>

3.1.5.2. print()#

The print function is a Python built-in function that output text. In Jupyter Notebook, typing the variable name displays the value, but to officially display output in Python, we use the print statement.

You can pass a string literal directly to print() as an argument:

>>> print("Please wait while the professor is thinking...")

Please wait while the professor is thinking...

Mostly, you pass variables to print() instead of a string literal:

greeting = 'hello world'

print(greeting)

You can also pass expressions to print():

>>> x = 10

>>> y = 2

>>> print( x**y )

100

>>>

print() also accepts multiple arguments separated by comma:

>>> name = "Dr. Chen"

>>> age = 35

>>> print(name, age)

Dr. Chen 35

>>>

You can also mix expressions with literals when printing using commas (a space between each item will be added):

name = "Bob"

age = 25

print("Hello,", name, "! You are", age, "years old.")

If you use concatenation (+) to join the arguments, you have to cast the arguments to string (note that concatenation does not add commas between arguments):

>>> print(name, age)

Dr. Chen 35

>>> print(name + age)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<python-input-4>", line 1, in <module>

print(name + age)

~~~~~^~~~~

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

>>> print(name + str(age))

Dr. Chen35

>>>

F-strings, also called formatted string literals, are string literals that have an f before the opening quotation mark. They can include Python expressions enclosed in curly braces. Python will replace those expressions with their resulting values. F-strings are more flexible and readable and therefore is in general preferred for string formatting:

>>> name = "Dr. Chen"

>>> age = 35

>>> print(f"Hi, {name}, you are {age} years old!")

Hi, Dr. Chen, you are 35 years old!

>>>

The end and sep parameters in the print function are used to control the output format. end (default to \n, the newline character) controls what character(s) are printed at the end of the printed text; sep (default to \\ for ) specifies the separator between the values that are passed to the print() function.

In the example below, we want to print the full path to your project folder by setting the sep parameter:

>>> import os

>>> print("C:\\", "User", os.getlogin(), "workspace", "dsm", sep="\\")

C:\\User\tychen\workspace\dsm

>>> import os

>>> print("/Users", os.getlogin(), "workspace", "dsm", sep='/')

/Users/tychen/workspace/dsm

>>>

In this example below, we want to print all the output in one line (because each print output by default has a new line character at the end of the line) by setting the end parameter to a space.

>>> for num in range(5):

... print(num)

...

0

1

2

3

4

>>> for num in range(5):

... print(num, end=" ")

...

0 1 2 3 4 >>>

3.1.6. Error Messages#

Divide by zero error:

>>> x = 100

>>> x / 0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<python-input-1>", line 1, in <module>

x / 0

~~^~~

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

>>>

Syntax error:

>>> import os

>>> print(f"Hello, {0s.getlogin()}! How are you?")

File "<python-input-12>", line 1

print(f"Hello, {0s.getlogin()}! How are you?")

**^**

SyntaxError: invalid decimal literal

>>> print(f"Hello, {os.getlogin()}! How are you?")

Hello, tychen! How are you?

>>>

3.1.7. Conclusion#

In this lecture, we covered lists, slice notation, how to grab things from an index, strings, print formatting, basic variable assignments, and basic arithmetic. Key Takeaways

Python supports basic arithmetic operations and variable assignments using intuitive syntax.

Strings can be created with single or double quotes and support indexing and slicing.

Print formatting allows dynamic insertion of variables into strings using the .format() method.

Lists are ordered sequences that support indexing, slicing, appending, and nesting.

3.1.8. Resources#

Python (programming language). (2024, February 20). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Python_(programming_language)